“Hailey!” I called to her and her eyes popped open. She saw me, leaned over and put a finger to her lips.

“We have to keep the noise down, coach. There’s nothing so far. I don’t want to scare ‘em.” She whispered down to me.

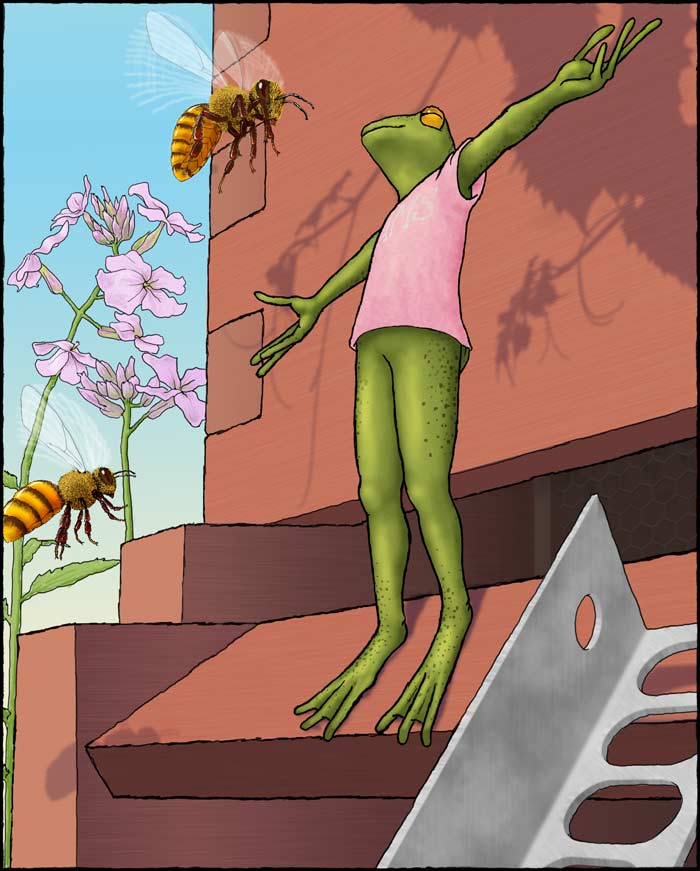

“I know! Your brother just made contact. He wanted me to give you a heads up.” I whispered back as best I could, excited as I was. She gave me a quick nod, then stood back up with her arms out. Her eyes darted from side to side. She looked worried. Wasn’t this going to be her first time handling bees? She’s an amazing tad, but she’s still a tad.

“Warren told me that if anybody can learn this stuff and pull it off, it’s his sister. He said you’ve got this.” She stood for a moment, then her mouth curved into a smile and both her thumbs went up.

She stood smiling with her arms out for a long while. Then, I thought I heard bees. Hailey already had her eyes locked on a spot out over the field. I followed where she was looking and saw them. It wasn’t a big cloud like we saw from the tree, it was a smaller group drifting towards us. It looked like they were changing positions in the cloud as they flew. Finally one broke away and flew closer to Hailey. It stopped before it reached her and just hung there in the air, looking. Hailey was motionless. That one bee drifted closer, till it was right in front of her. First it looked in her face, then it drifted back and forth along her arms getting close, then drifting back, getting close, then drifting back. They were both motionless, looking at each other. Then it dropped to the deck and walked around. It looked like it was looking for something back and forth along the deck. I have no idea how bees do what they do. This one moved about and finally went up to the entrance darting in and out several times before it flew away. I was shocked, and started to say something when Hailey gave me a quick, soft “Shhh!” She was still motionless.